Silver Valley dilemma:

Superfund -- solution or a bigger

problem?

Tribes & EPA want funds

to clean up

a century

of pollution

By Ken Miller

The Idaho Statesman

|

| Kim Hughes |

| North Idaho's Lake Coeur d'Alene is part of the 3,700-square-mile

Coeur d'Alene Basin, where the Environmental Protection Agency is studying

contamination problems caused by a century of mining. |

|

| Kim Hughes |

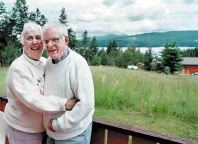

| Bob and Jeri McCroskey have their dream home in Harrison, overlooking

Lake Coeur d'Alene, and they are concerned that efforts to clean up the

area will be inadequate. |

|

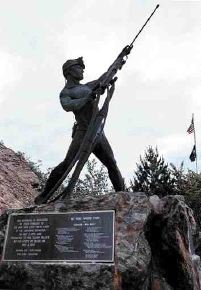

| Kim Hughes |

| This memorial is dedicated to the 91 men who were killed in

the nation's second-worst hard-rock mining disaster at Sunshine Mine on

May 2, 1972. |

Small-town Idaho isn't supposed to be like this.

Seven-year-olds are paid $20 to have blood drawn from the crook in their

arms. Toddlers read comic books warning them not to eat snow, suck icicles

or make mud pies. Playgrounds are sterilized.

Around the neat and trim residential homes, the yards have been dug

up, and trucked-in soil lies atop plastic liners -- more than 1,400 cubic

yards so far. Gardeners are told to grow only plants that produce edible

parts above ground -- no onions, carrots or potatoes. Inside the houses,

government-lent super-vacuums scoop up crud from the living rooms to be

studied in laboratories.

No, Kellogg is no normal small town. Nor is nearby Wallace. Or Smelterville.

Or Pinehurst.

All are nestled in the stunning beauty of the Gem State side of the

Bitterroot Range. And all are part of a spectacular gigantic downhill plumbing

system that continues to flush 100 years worth of contamination into the

Coeur d'Alene watershed.

Kellogg is ground zero for the area's worst mining pollution. The old

Bunker Hill smelter, where mountains of rocks were turned into a king's

ransom in minerals until a 1973 fire ruined the smelter's main environmental

filters, now is one of the nation's most infamous environmental Superfund

sites.

More troubling to Idahoans up and down the 50-mile Silver Valley is

that the whole drainage, also known as the Coeur d' Alene Basin, now is

thought of as a Superfund site as well. While the designation hasn't been

formalized, the basin nonetheless is considered one of the largest contamination

zones in the United States.

The Bunker Hill Superfund site in Kellogg is 21 square miles. At issue

now is how to deal with mining contamination in the rest of this 3,700-square-mile

valley. EPA and state officials agree recent federal court decisions have

cleared the way for the entire basin to be treated as if it were a Superfund

zone. The EPA said it won't take severe measures to clean up the region.

Rather, it said, it will work with the state to focus on contamination

"hot spots."

"We do at this point have the ability to use Superfund dollars if mining

in an area poses an unacceptable risk to human health and the environment,"

EPA Coeur d'Alene Basin Project Manager Mary Jane Nearman said Friday.

While she said a long-running lawsuit by the Coeur d'Alene Tribe and the

federal government remains in place to force mining companies to help pay

for the cleanup, she said a recent court decision has freed EPA to attack

expensive contamination problems across the basin as if they were part

of a larger Superfund area.

The problem reaches beyond North Idaho. All Idahoans will pay. Regardless

of whether the cleanup costs $4 billion, as some want, or $250 million,

the state must pay 10 percent of the cleanup.

On the ground

In her Studio Z salon in Wallace's historic Brooks Hotel, 47-year-old

Kathy Zanetti said she realizes that mining in the old days polluted the

Silver Valley. But she also said things aren't bad enough to consign the

massive Coeur d'Alene Basin to Superfund status, which would put it on

the same level as places such as New York's dreaded Love Canal.

"My family has been here for five generations in this valley," Zanetti

said as she worked with a customer in the hotel's salon. "... To say that

the lead contamination in this valley has created this huge health threat

just isn't right. I understand part of what they're doing, but (mining)

is also part of our heritage."

It's also part of the problem here, where almost everyone has ties to

the industry. Fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers worked in these

mines, built the homes, ran the hardware stores, and poured drinks for

generations. Almost all of it done with the paychecks from miners.

But that heritage has come at a price.

Bob and Jeri McCroskey have their dream home on the eastern shore of

Lake Coeur d'Alene in Harrison, where the contaminated Coeur d'Alene River

flows into one of Idaho's most prized natural assets. An abandoned Union

Pacific rail bed nearby was constructed with contaminated mine tailings.

"They claim they're cleaning it up, but they're not cleaning it up"

Jeri McCroskey said. "You've got to be very careful with this lake. All

the talk is about lead, but there are other minerals. You have to consider

how these contaminants work together. We're dealing with 100 years of contamination,

and it's not going to be solved overnight. There is no quick fix."

History and heritage

It's been more than 100 years since the owners of a local mercantile

store gave prospector Noah Kellogg $20 and a jackass to go find gold in

the local hills. Legend has it Kellogg's jackass hit paydirt, stopping

short in a creek to gaze at the glittery galena rocks.

And the Silver Valley was born. Cradled in the world's richest silver

lodes, mines sprouted throughout the basin, building fortunes not only

for the men who staked the local prospectors but also for the towns that

served them.

The mines helped win World War II, with thousands of tons of lead and

zinc hauled up from the ground. More lead and zinc come out of these mines

than any others in the country. There's a good chance that the lead in

your car battery, the zinc in the film in your camera, and the silver in

your heirloom cutlery came from these mines. More than $5 billion in minerals

has been unearthed here in the past century.

The Coeur d'Alene Mining District fast became one of the highest metal-producing

areas in the world; it also is one of the most contaminated, according

to the EPA. New technologies and environmental rules have reduced new contamination,

but the few remaining mines are being told they must pay for the sins of

their predecessors.

Pollution

Abandoned mines and mills cover about 600 square miles in the eastern

portion of the 3,700-square-mile Coeur d'Alene Basin. The Bureau of Land

Management has identified 1,075 areas impacted by 550 mines and tunnels;

46 mill sites; 170 rock dumps and pits; 28 inactive mine tailing areas

or ponds and two active tailing ponds; and 70 stream and flood areas affected

by mining.

As recently as 1964, 2,200 tons of mining waste flowed into the Coeur

d'Alene River every day. In recent times, the threat has been from airborne

lead that has contaminated the ground kids play on and the gardens tilled

by their parents.

In 1983, a decade after the fire in the Bunker Hill smelter coated Kellogg

with 1,000 tons of lead in just one year, Kellogg was declared one of the

nation's worst environmental disaster areas. A 21-square-mile "box" was

drawn around the town, and EPA put it on the Superfund list. That was no

surprise to Kellogg residents, who for years had been coughing in the yellowish

haze from the Bunker Hill smelter. The local landscape had lost its vegetation,

and the scenic river basin had been ravaged.

Today, there are fears that the pollution that suffocated Kellogg wasn't

confined to that now-notorious box. For example, an estimated 72 million

tons of contaminated waste sit at the bottom of once-pristine, 23-mile

long, Lake Coeur d'Alene.

"We in the valley will not continue to live as guinea pigs," said Coeur

d'Alene Tribe biologist Phillip Cernera, who is working on the natural

resources damage assessment in the basin. "The tribe's position has always

been that mining isn't the enemy. Pollution is the enemy, and cleanup has

to occur."

Kathy Johnson, studying the human-health impacts of the contamination

for the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, said lead is not a major

health threat in the lower part of the Coeur d'Alene Basin, which she called

a "very healthy, thriving ecosystem," with the exception of a higher-than-normal

waterfowl mortality rate.

Still, signs along the lakes in the lower basin near Lake Coeur d'Alene

caution anglers and others to take care when eating fish from the contaminated

waters and to keep children from playing with mud and dirt.

The EPA maintains it's too soon to declare the basin healthy, particularly

with the Coeur d'Alene Tribe producing data showing wildlife has been harmed

by the pollution, and soil samples showing lead levels above federal guidelines.

Health hazards?

Local health officials fear excessive lead poisoning from the mines

and from the 1973 Bunker Hill smelter fire have exposed the region's children

to dangerous contamination, which the government said could stunt their

physical and mental development. They also say the region no longer is

safe for some wildlife species.

"From an ecological perspective, it's in bad shape, and it varies in

severity, depending on the location," Cernera said. "We've got eight to

10 species of birds in our basin dying of lead poisoning. We've got fish

mortalities."

The tribe says it may cost $3.9 billion to clean up the basin, an estimate

that even the EPA says may be out of reach. So far, $87 million has been

spent cleaning up the Kellogg Superfund site alone, and EPA estimates another

$58 million will be needed.

The $3.9 billion cleanup estimate would finance massive removals of

contaminated dirt and reclaiming tainted waterways. The more modest $500

million to $1 billion cleanup would set aside money to attack "hot spots"

needing work rather than reclaiming the entire basin.

"Maybe $3.9 billion up front sounds like a lot of money, but you're

going to have to spend that much over time. Big money is going to be needed,

and it's going to be needed for many, many years," Cernera said.

Not so, said Holly Houston, executive director of the Mining Information

Office in Coeur d'Alene. Houston said the Coeur d'Alene Basin doesn't have

nearly the contamination problem of the Kellogg "box," and creating what

would be the nation's largest Superfund site would do more harm than good.

She said the state and EPA should concentrate on specific areas.

Houston and other Superfund opponents, including most elected local

officials and area business leaders, say the stigma of being a Superfund

site would discourage businesses from locating here and cripple tourism.

Sen. Jack Riggs, R-Coeur d'Alene, the Legislature's lone physician and

a member of the Governor's Task Force on Human Health Risk Assessment in

the basin, said it's illogical for the EPA to rope off the sprawling Coeur

d'Alene Basin as a Superfund site.

"We know there are some problems on the Coeur d'Alene (River). Why can't

we focus on those problems? The lake (Coeur d'Alene) meets federal drinking

water standards for lead. ... This certainly isn't a health issue," Riggs

said. "There are some who want to return the valley to a pristine state,

but that is an unattainable goal."

Who pays?

Federal and tribal officials have lauded Gov. Dirk Kempthorne and Steve

Allred, head of the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, for trying

to reach an agreement with the mining companies to help finance the cleanup

Allred said his goal is to reach a settlement with the mining companies

to help pay for the cleanup, among other objectives. He said the state

plan that DEQ's Johnson is working on, due to be completed by the end of

this month, will identify specific areas in the basin where Superfund money

should be spent.

"There would be those who would rather have a (basin-wide) Superfund

designation," Allred said. "We don't think that's necessary."

"The state is opposed to Superfund listing for a couple of reasons,"

Johnson said in her office, across from the giant Bunker Hill Superfund

site. "It's not that we're opposed to taking federal money for some reasons,

but Superfund can have some negative impacts."

Local business leaders say being a Superfund site would make it difficult

to recruit businesses. In addition, it's difficult to obtain bank financing

for projects in Superfund zones.

Cernera of the Coeur d'Alene Tribe said keeping people away from the

contamination isn't the answer.

"Posting signs to keep people away from the crud -- institutional controls,

they're called. Managing people around the contamination, we don't agree

with that. We don't want warning signs in our basin. We want people to

be able to use these areas," Cernera said. "Why should we be herded like

cattle into areas that are clean versus those that are not clean?"

Tom Fudge, unit manager of Hecla Mining Co.'s Lucky Friday Mine in Mullan,

is a member of the Shoshone Natural Resources Coalition, which opposes

a Superfund designation for the valley. He said the Superfund program doesn't

have enough money for such a massive cleanup.

"There are something like 2,000 sites on the list, and there's $1.5

billion in Superfund," he said. "You do the math. We're talking about low

levels (of contamination) that we think can be handled in a local manner.

The (mining companies) don't have $1 billion. I'm sorry, the money's not

there. End of story."

But Cernera said someone has to pay, and if the mining industry doesn't

have the money, Superfund is the only option.

Four major mining companies remain in the Silver Valley today -- Coeur,

Hecla, Sunshine, and Asarco. All are named in a lawsuit by the tribe and

federal government seeking money to clean up the basin, even though most

of the contamination was the result of mining by companies that no longer

exist.

Houston said forcing these miners and companies to pay for the cleanup

punishes the wrong people.

"I'm looking at people working for the companies today, and these are

not the people who put the contaminants in the system. Most weren't even

born when the contaminants were put in the system. ... These companies

can't afford to pay for everything they want to have done. People have

these assumptions these companies are made of money, and they're not."

Wallace banker Bill Dire Jr. joined his fellow Wallace City Council

members in voting unanimously last month to urge EPA to refrain from designating

the basin as a Superfund site.

"That would devastate North Idaho," Dire said. "It's politics, plain

and simple."

Dire doesn't deny the area has been polluted: "When I was a kid, the

South Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River used to run a murky gray color, and

we didn't call it the South Fork; we used to call it 'Lead Creek.'

"But to see it today, compared to 15 years ago, you can see how much

it has cleaned up. Mother Nature has incredible healing power, which the

environmentalists don't want to believe."

Contact Ken at 377-6402 or kmiller@boise.gannett.com

|