Leisenring recalls encounters

with union leaders

By JEFF LESTER, Senior Writer November 16, 2004

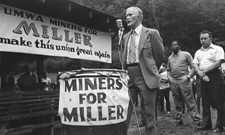

| Reform candidate Arnold Miller speaks during a rally in his successful 1972 campaign against UMWA President Tony Boyle. (Photo provided by UMWA) |  |

Ted Leisenring Jr. negotiated - and sometimes fought - with four different

leaders of the United Mine Workers of America during his nearly 30-year

presidency of Westmoreland Coal Co. His first encounter with the union's

greatest legend, four-decade president John L. Lewis, came only a few years

after the young Leisenring had started his career as a miner and UMWA member

in the early 50s, author Dan Rottenberg writes in the 2003 book "In the

Kingdom of Coal." It was at the Glenbrook mine in Harlan County, Ky., Rottenberg

writes, that Leisenring, who was still attending UMWA meetings, first encountered

militant union leaders. The bosses of the union local were two cousins

named Deaton who would harass miners and foremen alike, calling wildcat

strikes at will and actually beating up management personnel at times.

Leisenring's namesake father retired from the company's presidency

abruptly in late 1951 due to ill health, and the young man was transferred

to western Pennsylvania, then to Philadelphia. But three years later, young

Leisenring was still seeking a solution to the Deaton problem.

He looked for help from his father's longtime colleague Ralph Knode, who had become president of both Stonega Coke & Coal Co. and Westmoreland Coal Co. Knode and Leisenring personally approached John L. Lewis.

Lewis, in his 70s, greeted the 28-year-old upstart with courtesy but seemed to dismiss the Deaton problem. He told Leisenring that in time, the issue would seem to him as insignificant as "a mosquito trying to bite the ass of an elephant."

Yet, two months later, Leisenring learned that Lewis had quietly transferred the Deatons to the midwest.

Rottenberg's book delivers a richly detailed portrait of the larger-than-life Lewis, once an aspiring actor, and his masterful 40-year leadership of a union he knew would eventually shrink as mechanization slashed jobs but improved the lives of the remaining miners.

The book fills a void in the public's knowledge of Lewis, who was infinitely better to deal with than his successors, Leisenring said in a recent interview. "I've looked, but never found, a definitive biography of Lewis. He was an absolutely amazing man."

Lewis' leadership of the miners' union did much to launch the age of labor in American industry, helping to create the mighty AFL-CIO.

The height of the UMWA's power, arguably, was during World War II, Leisenring said. At one point, President Roosevelt called Lewis anti-American for putting a half-million miners on strike to protest frozen wages while the nation's war effort needed coal. But Lewis was brave enough to stand up for his members, Leisenring said.

The UMWA and coal operators have often found ways to work together, despite all the publicity about those times when they were at odds, Leisenring said. "Lewis played both sides against the middle better than anyone I've ever known."

But by the mid-50s, Rottenberg writes, Lewis' failing health emboldened his lieutenants to begin jockeying for position as they anticipated his retirement.

In the summer of 1958, Stonega attempted to reduce the number of loading machine helpers at Glenbrook, prompting a five-week wildcat strike. By then, Leisenring's nemesis Jack Deaton was back in the union's District 19, which covered Kentucky and Tennessee. Deaton was working with the district's secretary-treasurer Albert E. Pass, who Rottenberg describes as a "stocky, cold-eyed little man" nicknamed "Little Hitler" by his own union brothers.

Pass was said to have bankrolled a group of miners who would terrorize coal operators who refused to sign union contracts by dynamiting or burning their tipples and physically attacking some operators.

Pass was also closely allied with Lewis' longtime lieutenant Tony Boyle, according to Rottenberg.

The strike was settled when Stonega agreed to keep its existing number of helpers on the payroll, and Pass and Deaton guaranteed that Glenbrook would produce at least 1,800 tons of coal per day.

But six months later, Leisenring found himself threatening to close the mine because it averaged only 1,407 tons per day and hadn't exceeded 1,700, Rottenberg writes.

Leisenring became president of Stonega in 1959 and took over control of Westmoreland from Knode two years later.

The decade-and-a-half since World War II had seen literally thousands of coal companies consolidate into a relative handful of big companies with holdings in several states. Westmoreland shut down the last of its Pennsylvania mines to focus, along with Stonega, on Virginia and West Virginia.

Lewis welcomed such consolidation as progress. Rottenberg writes that in 1959, Lewis remarked, "When we had 11,000 producing entities in the coal industry, no one operator could speak for the industry as a whole, on legislation, on wages, on anything. Now the big companies give national leadership to the industry side."

THE BOYLE YEARS

In 1960, the elderly Lewis "retired" but maintained his influence for a few more years. Knode and Leisenring learned that he wanted to eventually name Boyle as the new union president.

"I would hate to find him running that union," Leisenring said of Boyle in a conversation with Knode. "He'll never have the intelligence, or a fraction of it, that John Lewis has."

Knode, who had maintained a friendship with Lewis, tried to convince him to choose someone else, without success. When interim president Thomas Kennedy died in 1963, Boyle ascended to the office.

One year later, Leisenring had consolidated the power of his operations by combining Stonega and Westmoreland into a single large company.

The union had real strength with Lewis at the helm, Leisenring says. By contrast, Boyle was the epitome of a "black Irishman" who had "no sense of humor, no emotion."

Rottenberg writes that Boyle did not relate to the union rank-and-file and built walls around himself as he increasingly saw real or perceived enemies all around. He moved the union's 1964 national convention from a traditional site near the coalfields to Bal Harbour, Fla., and lengthened it to 11 days, so that only delegates whose expenses were paid by the union could attend.

Boyle most notably displayed his lack of Lewis' personal touch with rank-and-file miners in his response to a 1968 explosion that killed 78 miners at Farmington, W.Va., according to Rottenberg.

Boyle showed up four days later, offering only a few brief comments about the "inherent danger" of mining. He defended the operator, Consolidation Coal Co., as one of the best the union worked with in terms of cooperation and safety, seemingly unaware that Consolidation had violated federal safety regulations.

The following year, a challenge to Boyle's UMWA leadership spawned the most notorious episode in the union's history.

Pennsylvania UMWA official Jock Yablonski ran for the presidency as a reform candidate. Albert Pass and other union officials were later convicted for conspiring to murder Yablonski, his wife and daughter - a crime allegedly ordered by Boyle.

Boyle was convicted in 1974, but Leisenring has doubts about the degree of his culpability in the murders. It's possible that Boyle was guilty only of remarking out loud that Yablonski ought to be killed, in front of district officials who took that as an express order, he said.

However, Rottenberg writes that according to trial testimony, Boyle allegedly answered, "Yeah," when Pass suggested that District 19 would murder his rival.

REBUILDING THE UNION

As frustrating as Boyle could be to deal with, Leisenring had no more affection for his successor, Arnold Miller.

Miller, who ran the union from 1972-79, wanted to "democratize" the UMWA by replacing many district officials and giving union locals a greater say in negotiations.

Leisenring headed the National Coal Association in the early 70s, and found himself chairman of the Bituminous Coal Operators' Association, the industry's negotiating body, in the late 70s. He was on the front lines when, in 1977, the UMWA launched one of its most significant strikes, one that idled 180,000 miners for 111 days and ultimately sparked intervention by President Jimmy Carter.

Reaching a contract meant negotiating with UMWA international officials, district officials and rank-and-file miners at the same time, each with differing priorities, Rottenberg writes. Leisenring calls this the most frustrating experience of his career.

Leisenring speaks more fondly of Miller's successor, longtime Appalachia resident Sam Church, a onetime Westmoreland miner whose negotiating style, Rottenberg writes, seemed more suited to foster trust and respect between miners and managers.

Rottenberg recounts a story, early in Church's career as union president, in which the UMWA picketed Westmoreland while trying to organize a Kentucky mine on land owned by Westmoreland's sister company, Penn Virginia Corp.

Church flew to Southwest Virginia and led a group of Westmoreland employees through his own union's picket lines, It was, as former UMWA official Joe Brennan suggested, "Church's way of saying that Westmoreland had always kept its word to the union, and the union wouldn't forget that," Rottenberg writes.

But by the time Church rose to leadership, the union's power was all but gone, in Leisenring's opinion.

Church served the remainder of Miller's last term after his retirement due to ill health in 1979. Church lost his bid for another term, defeated in 1982 by attorney Richard Trumka, who served longer as UMWA president than anyone except Lewis.

Rottenberg's book does not mention Trumka or his vice president, current UMWA President Cecil Roberts, who gained national recognition for bringing nonviolent civil disobedience methods to the 1989-90 Pittston Coal strike.

However, the legacy of that strike - 1992 federal legislation that dramatically

changed coal companies' health and retirement obligation to retired miners

- created new financial burdens that helped convince Westmoreland to shut

down its unionized eastern operations, according to Rottenberg.

©Coalfield.com 2004