Leisenring was last of a breed

By JEFF LESTER, Senior Writer November 16, 2004

|

|

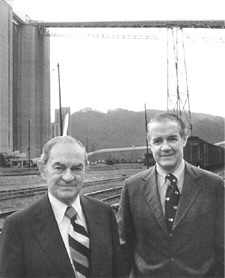

| Then-Westmoreland President Howard Frey, left, and Leisenring posed at the Bullitt transloader near Appalachia for this photo in the 1978 annual company report. | Westmoreland Coal Co. CEO E.B. 'Ted' Leisenring Jr., left, appears

with President Pemberton Hutchinson in the company's 1986 annual report

to shareholders.

|

Ted Leisenring Jr. was born to an industrial dynasty, grew up among

the mansions of Philadelphia's tycoons and rubbed elbows with their sons

at Yale University. He was the fifth Leisenring who eventually rose to

top management in the family business - coal mining. But when he graduated

from college in 1949 and took his first position in the corporate hierarchy,

he had no interest in sitting at a desk and giving orders. At 15, when

America had just plunged into the uncertainty of a world war, Leisenring

had accompanied his father on a business trip to Wise County, where he

first entered a coal mine. "Nothing could quite match the masculine excitement

of going underground in wartime, or the sight of miners with their soot-covered

faces, hard hats and cap lamps," writes Dan Rottenberg in his 2003 book

on the family's role in the coal industry, "In the Kingdom of Coal." "Young

Leisenring was permanently smitten."

Eight year later, fresh from earning his degree, Ted Leisenring yearned

to go underground again, and his father was happy to oblige. He started

work for Stonega Coke & Coal Co. in Big Stone Gap as a survey crewman,

measuring coal seams.

"I was delighted to join the business," Leisenring said in an Aug. 13 interview. "My father had taken me into the mines. I was ready. It was a complete shift in my life. I submerged myself in the business."

After about a year, Leisenring surprised Stonega general manager Harry Meador with a request - he wanted to become a miner and join the United Mine Workers of America.

Leisenring says he wanted to learn by getting his hands dirty with fellow miners. "My father was delighted. Meador was horrified . . . It really paid dividends later."

The only other major coal executives Leisenring can think of who actually worked in mines themselves were old friend Herbert Jones, president of Amherst Fuel Co., and A.T. Massey head Morgan Massey.

In 1950, Rottenberg writes, 24-year-old Leisenring became a hand loader in Stonega's Imboden mine, where he became friends with miners Don Givens, a Powell Valley resident, and Givens' cousin Hagy Barnett, who still lives in Imboden.

Leisenring later worked at Derby and in Stonega's Glenbrook mine at Harlan, Ky. Meanwhile, he married Julie Bissell and they lived in Big Stone Gap almost two years, giving birth to their first child in Kingsport, Tenn.

CHANGING TIMES

Ted Leisenring Jr. inherited a business legacy that covered both sides of Pennsylvania and journeyed to Virginia and Kentucky.

Under his nearly 30-year leadership beginning in 1959, Stonega and its corporate cousin Westmoreland Coal Co. weathered storms that Leisenring's predecessors could not have foreseen. He responded by taking the family business in new directions - geographic and otherwise - and following a handful of high-risk hunches that paid off.

Leisenring was at the helm in the early 60s when the growing environmental movement sparked creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. At the same time, the war in Vietnam planted the seeds for a national economic downturn.

In 1964, Leisenring merged Stonega and Westmoreland into a single company.

Throughout the decade, Rottenberg writes, Leisenring took advantage of the companies' long-standing relationships with overseas markets to offset volatile American markets. During this time, Leisenring moved to expand Westmoreland's coal exports by acquiring C.H. Sprague & Son Co., a leading exporter with 90,000 acres of low-sulfur metallurgical coal in West Virginia.

In the spring of 1970, Leisenring's standing in the industry was such that he led a delegation of coal executives to the Soviet Union to provide advice on improving the communist nation's antiquated mining methods.

Later that year, he made another decision to expand Westmoreland's operations, one that proved critical to the company's survival - and fateful for its Appalachian mines.

Leisenring gambled millions on mining the Powder River Basin of Wyoming, Montana, Utah and Colorado for its low-grade but extremely clean-burning lignite.

It was a smart move with a great irony at its core, according to Rottenberg. The coal would become more competitive as the EPA tightened coal-fired plant emission standards, but the large-scale surface mining it required would anger environmentalists by tearing up giant swaths of pristine land.

Heading west also meant getting away from the UMW's now-diminished influence, but that wasn't a prime motivation, Leisenring says.

It was always in the company's best interest to get along with the UMW while the union was all-powerful. Westmoreland only looked for other opportunities "when we saw the jig was up for the union," he said. "Otherwise, we couldn't compete."

After four years of negotiating with the Crow Indians and other Montana surface owners, struggling with environmentalists and pouring millions of dollars into the investment, Westmoreland finally began shipping coal from a giant Montana surface mine.

While Westmoreland was launching its western operations, the Nixon administration had nearly crippled the coal industry by imposing price controls to stem inflation, Rottenberg writes. But that blow was soon softened by an unforeseeable blessing in disguise.

The 1973 Yom Kippur war against Israel prompted Middle Eastern oil producers to cut off supplies to Israel's allies. The resulting oil shortage spurred the White House to compensate by lifting price controls on coal to promote increased production.

And so began the most recent great coal boom, with companies big and small scrambling to mine as much as they could as quickly as possible.

Management is a combination of basic, sound business practices and knowing how to play a hunch, Leisenring acknowledges. "You must see the trend you're in, whether it's permanent, temporary or long-term, and you must have an instinct for how soon a trend will turn . . . Some people are good guessers, some are not."

The boom lasted about four years. It began to fizzle in 1978 in the midst of three events - an easing of the oil restrictions, competition from foreign coal and a labor contract concession in which U.S. operators guaranteed lifetime health care for their own union employees and retirees. The latter seemed manageable at a time of record profits.

The Japanese modified steel production methods to use lower-grade coal from Australia and Canada, prompting American steel makers to shop outside the country as well.

Meanwhile, dramatic production increases during the mid-70s left American coal companies with massive stockpiles of product. Westmoreland was forced to lay off 1,500 employees at its eastern operations.

In the early 80s, American coal operations got a brief bounce from selling stockpiled steam coal to overseas power producers, Rottenberg writes. It ended when the excess inventory declined, and in 1984 Westmoreland began phasing out its West Virginia mines.

Finally, the 1978 promise that each company would provide lifetime health care for its own miners and post-1975 retirees - and its predecessors, the 1950 and 1974 agreements that created the union's lifetime health and retirement funds - took on a new meaning in the wake of the 1989-90 UMW strike against Pittston Coal for reneging on some of its retiree obligations.

In 1989, Congress began debating legislation that would require surviving coal companies to pay into a benefits fund for "orphaned" miners whose employers had gone out of business. It passed in 1992.

The cost of the new benefits plan was staggering, Rottenberg writes. It accelerated a wave of company shutdowns, each increasing the burden on remaining operators.

Leisenring retired in 1988 at age 62, turning the CEO duties over to Pemberton Hutchinson but remaining on the board of directors.

Five years later, Leisenring sold most of his Westmoreland stock, fearing the company could no longer survive, according to Rottenberg. In 1994 Westmoreland declared bankruptcy, listing liabilities of more than $100 million, mostly owed to the miner benefit funds.

LEGACY

That same year, Chris Seglem took over Westmoreland after helping run its Colorado operations for 14 years. He moved quickly to eliminate the company's eastern operations, choosing to focus on western coal. Within five years, Seglem had settled the health benefit obligations, brought the company out of bankruptcy and put it back on the road to profits, where it remains today.

Leisenring admits the journey has been remarkable - from an industry based on underground mining of Appalachian coal to one largely dependent on massive strip mining in the west. But Seglem's ability to save the company vindicates Leisenring's decision three decades earlier to gamble on yet another new production source. The change in the industry is "perfectly astonishing," he said.

Mining has always been a risky venture, both for investors and for laborers facing danger under and aboveground. The risks, as Big Stone Gap and Appalachia have learned, include losing one's livelihood and struggling to preserve one's community.

During the turbulent years of his leadership, Leisenring had chances to sell out and walk away, notably one from Standard Oil of Indiana. "We weren't interested," he said. "I had fought all my life for the company's potential."

But Leisenring found himself the last of a breed, with his son having found a successful career in technology after a brief stint in sales for Westmoreland. It was an understandable choice, the father said.

Leisenring last visited Big Stone Gap in 2001, when he shared stories of the old days with Don Givens, Hagy Barnette and Harry Meador Jr. Coal Museum proprietor Beecher Powers.

Visiting is bittersweet, he admitted. "I'm reminded of what was there and is no more."

But Wise County seems resilient to Leisenring. The community seems to have realistically assessed the trends of coal mining and weathered the storms fairly well, he believes.

After decades of contending with market upheaval, four union leaders, a United States president and all sorts of other challenges, Leisenring gives a surprising answer when asked to name the most exciting moment of his career.

Those early years in Big Stone Gap saw him begin his work in coal, make friends with miners, marry his beautiful wife and start a family, he said. "It was the happiest part of our lives."

©Coalfield.com 2004